Violinists face a silent adversary that strikes not at their craft but at their very ability to perform it. According to recent data from occupational health databases focused on musicians, violinists suffer the highest rates of cervical spine disorders among all instrumentalists. This unsettling trend reveals the physical toll exacted by years of perfecting their art, often at the expense of their musculoskeletal health.

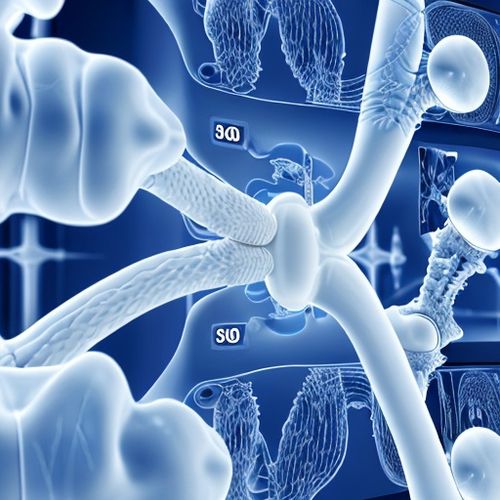

The demands placed on a violinist's body are unique and unrelenting. Unlike pianists or wind instrumentalists who maintain a more neutral head position, violinists must constantly tilt their heads to secure the instrument between chin and shoulder. This sustained asymmetrical posture, often held for hours during practice and performance, creates chronic strain on the cervical vertebrae. Over time, the cumulative effect manifests as degenerative changes, herniated discs, or chronic pain syndromes that can prematurely end careers.

Medical researchers have identified this phenomenon as "violinist's neck," a specific occupational hazard characterized by muscle imbalances, nerve compression, and accelerated spinal degeneration. The problem frequently begins conservatively - perhaps as occasional stiffness after long rehearsals - but progresses insidiously until musicians find themselves battling persistent pain that interferes with both performance and daily life. What makes these injuries particularly devastating is their impact on the delicate physical coordination required for virtuoso playing.

Orthopedic specialists who treat performing artists note that the violin's very design contributes to the problem. The instrument requires maintaining what physicians call the "violinist's triangle" - the complex relationship between head tilt, shoulder elevation, and arm positioning. This unnatural posture places approximately 10-15 pounds of rotational force on the cervical spine, equivalent to hanging a medium-sized bowling ball off the side of one's neck for extended periods. When combined with the vibrato motion and rapid position changes required during performance, the spine endures repetitive microtraumas that eventually take their toll.

The data reveals troubling patterns - professional violinists typically develop symptoms in their late 20s to early 30s, just as their careers begin to peak. By their 40s, many report chronic pain that requires medical intervention. Female violinists appear particularly susceptible, possibly due to generally smaller neck musculature and the added postural challenge of accommodating bust size. Orchestra players face greater risk than soloists due to the physical constraints of ensemble seating and the grueling schedule of rehearsals followed by performances.

Conservatories and music schools have begun implementing preventive programs, but change comes slowly in tradition-bound musical pedagogy. Many young violinists still learn through methods developed centuries ago, when understanding of biomechanics was primitive. Modern teaching increasingly incorporates Alexander Technique, ergonomic instrument supports, and targeted strength training, yet these measures often reach students only after poor habits have become ingrained.

The financial and emotional consequences can be devastating. A concertmaster unable to turn pages due to cervical radiculopathy, or a studio musician who can no longer endure three-hour recording sessions represents not just personal tragedy but significant economic loss. Insurance claims reveal that musculoskeletal disorders account for over 60% of disability claims among professional violinists, with cervical spine issues leading the category.

Technological solutions have emerged, from lightweight carbon fiber instruments to innovative chinrest designs that distribute pressure more evenly. Some luthiers now offer customized instruments with adjusted neck angles for players with existing conditions. Physical therapists specializing in performing arts medicine have developed targeted rehabilitation protocols, combining manual therapy with exercises that address the unique postural demands of violin playing.

Yet the core dilemma remains unresolved - the human body did not evolve to hold the violinist's position for hours daily over decades. As the medical data continues to accumulate, the music world faces difficult questions about how to preserve both artistic tradition and musicians' health. Perhaps future generations of violinists will benefit from redesigned instruments and revolutionized training methods, but for now, the neck pain concerto plays on for countless dedicated artists.

The situation calls for greater collaboration between medical professionals, instrument makers, and music educators. Only through such interdisciplinary efforts can the next generation of violinists avoid becoming statistics in the occupational hazard database. For current professionals dealing with cervical issues, early intervention and proper ergonomic adjustments may help prolong careers that would otherwise fall victim to the physical demands of their beautiful but biomechanically unforgiving art.

By Ryan Martin/Apr 14, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 14, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 14, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 14, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 14, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 14, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 14, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 14, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 14, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 14, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 14, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 14, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 14, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 14, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 14, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 14, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 14, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 14, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 14, 2025